It’s often said that there are two types of writers. The plotter plans everything out in advance. They know exactly what’s going to happen before they begin to write their first draft. In contrast, the discovery writer (or pantser) gets an idea and starts to write, developing the story as they go.

In truth, most writers are somewhere between these extremes. I prefer planning first, but from experience I know that the story will change as I write it. I’ll see how my planning doesn’t quite work, or I’ll figure out an alternative path for the story. Sometimes I’ll write an off-the-cuff comment (maybe something a character says or a throw-away piece of world-building) and my mind will run with this, changing huge sections of the book.

With this new project, I want a large-scale story (a space-opera with multiple main characters and events happening across different planets and spacecraft). Before I start writing I want to have a coherent idea of where the story is going.

And to plan this I need to know what kind of story I want to tell.

Taking another step back, I need to understand what I enjoy in both reading and writing. What draws me to a book? And (more importantly) what keeps me reading?

Another way of approaching this — what makes me want to stop reading?

I almost always finish reading a book once I’ve started, even if I’m not enjoying it. Sometimes I’ll find something in the characters or the story that intrigues me enough to continue through poor writing. Sometimes I’ll tell myself the book will get better (note to self: it rarely does). At other times I’ll use it as training, examining why I’m no longer engaged with the book.

But there have been times I’ve given up on books part way through. On the few occasions this has happened, it’s always been because I no longer cared what happened to any of the characters.

This tells me something about my reading habits. I might be drawn to a book by an intriguing set-up or concept, but it’s the characters that keep me reading.

It’s similar in my writing. Some of my most memorable times writing have been when I’ve been putting characters through emotionally hard times.

I’ll give you an example. In my Dominions series, I knew I wanted to put the main character in a position where, whatever choice he made, someone important to him would die. He couldn’t save them both, no matter how much he wanted to. I wasn’t going to let him suddenly find a way to get around the problem — this decision would have a serious impact not only on the story but also on the character.

And it’s that impact that was important. My character’s decision influenced the plot in key ways, ultimately influencing the way the whole series concluded.

So this choice was a plot moment, but it was also a very important character moment.

I’ve thought on this a great deal, and I’ve come to view story as the interplay between plot and character. Plot is the stuff that happens. I can describe a plot by saying ‘this happens and then this happens and then this happens’. It’s a list of events. But they don’t become a story until I introduce characters. These characters have to interact with the plot, reacting to these events, making decisions that influence future events.

If plot is ‘stuff that happens’, then the characters are the ones that let the reader experience that stuff. The plot only has meaning when characters are added.

It’s worth saying that these characters have to resonate with the reader, too. They have to be real. They might not all be likeable, but as readers we have to be invested in their arcs, in their growth or their descent.

As I plan this new series, I need to focus on character. Yes, there will be galaxy-spanning events, with the whole of humanity in danger. But if I want to make readers care, I need to show these events through engaging characters. If I want readers to relate to what is happening, I need to use characters to bring these immense events down to a personal level. A huge space battle could be exciting in theory, but put a new recruit in the middle of the battle as they struggle with the loss of their best friend, and now it’s emotional. Now it’s real.

So I have a starting point — characters as the primary focus, reacting to and driving external events. But how do I actually plan anything?

More on that next time.

I first became aware of this idea when I stumbled upon Gilden Fire by Stephen Donaldson. Having recently read his original Thomas Covenant trilogy, I was intrigued by this slim volume. In the introduction, Donaldson explained that Gilden Fire was originally going to be a chapter in The Illearth War. But while he was pleased with the writing, the story in the chapter didn’t involve the main character himself. Donaldson thought it would break the flow of the book, and so it was cut. It was only later that he revised it and released it as its own story.

I first became aware of this idea when I stumbled upon Gilden Fire by Stephen Donaldson. Having recently read his original Thomas Covenant trilogy, I was intrigued by this slim volume. In the introduction, Donaldson explained that Gilden Fire was originally going to be a chapter in The Illearth War. But while he was pleased with the writing, the story in the chapter didn’t involve the main character himself. Donaldson thought it would break the flow of the book, and so it was cut. It was only later that he revised it and released it as its own story. There’s little we can do about the current situation, beyond following whatever those in charge are suggesting (or ordering). But that doesn’t stop us worrying. It’s natural, in any strange situation, to hunt for a solution, even when there is nothing within our own reach. And this can increase our anxiety—which leads to all sorts of health issues, both mental and physical.

There’s little we can do about the current situation, beyond following whatever those in charge are suggesting (or ordering). But that doesn’t stop us worrying. It’s natural, in any strange situation, to hunt for a solution, even when there is nothing within our own reach. And this can increase our anxiety—which leads to all sorts of health issues, both mental and physical. Throughout history, stories have been used to educate. The tale of a successful hunt helps others develop and refine their own hunting skills. The sad story of a villager who ate the wrong kind of berry acts as a warning. The stories we read to our children help them make sense of the world.

Throughout history, stories have been used to educate. The tale of a successful hunt helps others develop and refine their own hunting skills. The sad story of a villager who ate the wrong kind of berry acts as a warning. The stories we read to our children help them make sense of the world. It’s often said that to truly understand someone, you need to walk in their shoes—and stories are a powerful way of doing this. Vicariously, we can live through the pressures of a high-powered job, or the daily grind of raising a family on a meagre wage. We can experience being lost in an alien environment, or living amongst those different to ourselves, or coping in a world where our beliefs are not shared by the majority. We can get a glimmer of understanding into why someone may turn to crime, or shut themselves off emotionally from others, or desperately seek acceptance.

It’s often said that to truly understand someone, you need to walk in their shoes—and stories are a powerful way of doing this. Vicariously, we can live through the pressures of a high-powered job, or the daily grind of raising a family on a meagre wage. We can experience being lost in an alien environment, or living amongst those different to ourselves, or coping in a world where our beliefs are not shared by the majority. We can get a glimmer of understanding into why someone may turn to crime, or shut themselves off emotionally from others, or desperately seek acceptance.

And, as with any bunch of co-workers forced together, there are tensions. Some of them get on well with others, but there’s a lot of animosity just beneath the surface. Just like any other work environment.

And, as with any bunch of co-workers forced together, there are tensions. Some of them get on well with others, but there’s a lot of animosity just beneath the surface. Just like any other work environment. And this tells us that nowhere is safe. Even if characters are together, in brightly-lit familiar rooms, they’re still in danger. We don’t need to peer into the darkness looking for monsters, because they could leap out of anywhere, at any time.

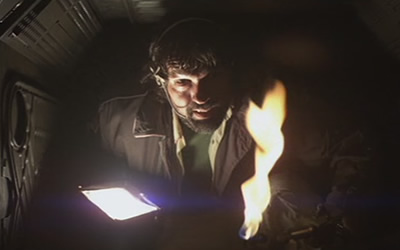

And this tells us that nowhere is safe. Even if characters are together, in brightly-lit familiar rooms, they’re still in danger. We don’t need to peer into the darkness looking for monsters, because they could leap out of anywhere, at any time. The rest of the crew are following his progress through the ducts. They have audio communication, but the only visual is on a map, with a marker to indicate his position. And then a second marker appears, indicating the alien’s position—and it’s closing in on Dallas. They yell for him to get out, but as the alien approaches there’s nothing they can do to prevent the inevitable.

The rest of the crew are following his progress through the ducts. They have audio communication, but the only visual is on a map, with a marker to indicate his position. And then a second marker appears, indicating the alien’s position—and it’s closing in on Dallas. They yell for him to get out, but as the alien approaches there’s nothing they can do to prevent the inevitable. But she makes it. From the shuttle, she sees the Nostromo explode—and then realises she’s not alone on the shuttle. The alien is with her.

But she makes it. From the shuttle, she sees the Nostromo explode—and then realises she’s not alone on the shuttle. The alien is with her.